How to commit code to version control systems… I suspect that there are at least as many approaches as there are people making software. Nevertheless, it is a topic worth to explore, and to challenge. Don’t expect an article that is exclusively talking about version control though, if anything this is a story on teamwork.

In this article you will learn what benefits you gain from making your commits small, sometimes even ridiculously small. In spite of the benefits, there are skeptics of reducing the size of your commits. The most principled objection against doing so, is that it supposedly would leave the software system in an inconsistent state. Concerns like those should be framed in the context of people working on software at an ongoing pace, so that’s what we’ll do.

Throughout this article you will find some useful heuristics to help you guide your own decision-making.

With those in mind, I hope you will join me in reducing the commit size in any project you are involved with, and that you will make “commit early, commit often” your mantra.

Are you ready to commit yourself?

Let’s go!

Make commits small

Picture this: it’s Tuesday a week from now. Your schedule is free of meetings for the entire morning: you will have all the attention to get started on fixing a big problem.

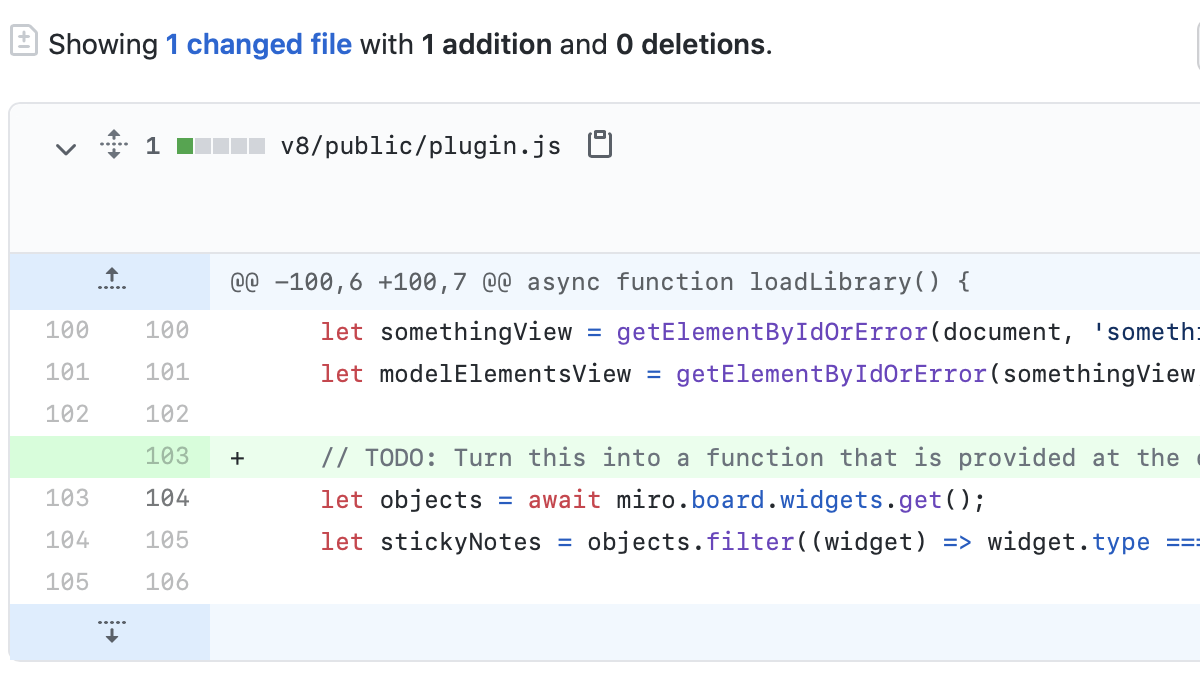

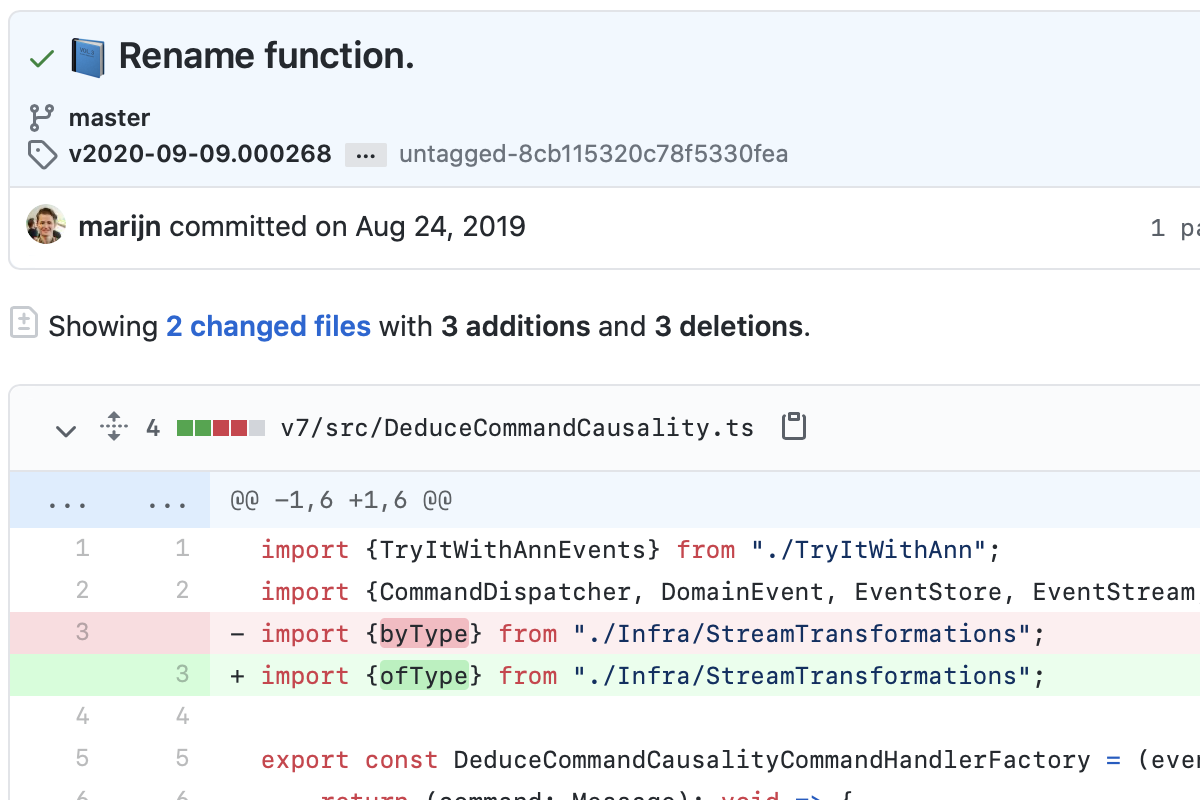

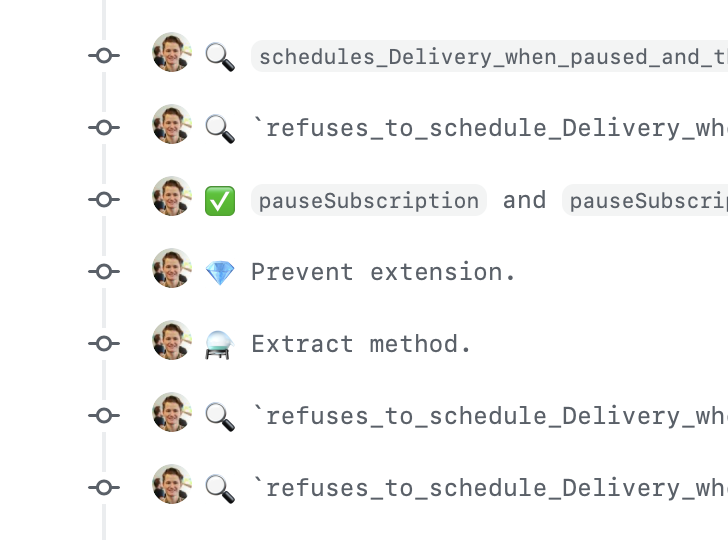

After opening up your laptop and booting your IDE you start to ponder where to get started. Perhaps you add some internal documentation, to clarify the goal of what you are trying to achieve. Or maybe the other way around: you draft some end-user documentation that describes how to use the intended solution. You might write a test that proves the existence of a bug. Or you start with some sense-making refactoring: introduce a variable here, extract a function there; Rename a function here, inline a constant there.

Each of these alterations constitutes an improvement to the system at large. That is why all of them deserve to be committed to your VCS, independently. Doing so will make your commits smaller and narrower in scope, which has a number of benefits:

-

Reduced cognitive load: If there is less going on, it becomes easier to grasp what a change is all about.

-

Easier to revert: When you commit more frequently then there are more points in history you can return to with the click of a button.

-

Transparent progress: It becomes easier for colleagues to follow what you are up to when you push a few commits every hour rather than one per day.

-

Storytelling in code reviews: By committing frequently you tell the story of how you arrived at the solution so far: each commit acts as a sentence saying what the next discovery was.

-

Safetynet for testing: If you commit a failing test and push it, then your colleagues are able to verify (assuming CI) that the test is not susceptible to false positives.

-

Less shallow remarks: Smaller changes are more inviting to comment on than large changes, this reduces shallow remarks such as “Looks good to me”.

-

More detailed commit messages: The commit message that accompanies a change will cover fewer things which invites the author to describe the change itself in more detail.

In short, turning each thought you have into some kind of mutation in the code base, and committing that change, is a great way of sharing knowledge in a sustainable and transparent fashion. Which brings us to the first heuristic (i.e. rule of thumb):

Turn each thought you have into some kind of mutation in the code base, and commit that change.

Examples of right-sized commits

-

Any bit of documentation: A one line comment with a todo item; a paragraph in the API docs in the function annotations; a decision in a

DECISIONSfile; or the initialREADME.

-

Automated refactoring: A single automated refactoring such as: extract method; introduce variable; inline function.

-

Test specification: An empty test case definition that will report as incomplete in the test runner; a test specification; a series of examples;

-

Discrete change: Increasing a threshold value; solving a bug; implementing one or more test cases;

-

Copy improvements: A translation of the UI elements into a different language; a hard-coded copy change;

-

Configuration changes: Usage of environment variables; Renaming an environment variable; updating some settings; new wiring of services;

-

Removals Removal of duplicate code; deleting obsolete code; killing useless tests; discarding an unused feature;

-

Dependencies: Updating existing dependencies; installing new dependencies; removing obsolete dependencies;

-

Codestyle improvements: Switching from tabs to spaces; converting snake_case to camelCase; apply a style guide;

Feel free to combine some of these types in a single commit, as long as the change remains congruent and focussed. Being dogmatic is never helpful.

Ways to find right-sized commits

Perhaps you wonder where to draw the line when doing multiple things at once. One way to look at it: automated changes (e.g. refactoring, dependencies, codestyle) should always be committed independently, in order to be able to ignore their details when reviewing.

That makes for an excellent heuristic:

Never combine changes produced by machines with changes produced by humans.

Can we think of a situation in which this heuristic wouldn’t apply? How about an entry in a changelog (human-made) that accompanies upgraded dependencies (machine-made), in order to address a security concern caused by a package the project depends on. A purist might say that context about the change should be part of the commit message, and not be entered separately. Yet I am inclined to do both in such a situation: (1) add that entry, and (2) copy that message as the description of the commit message. Which brings us to another heuristic:

If it is important enough to put it in the commit message, then it is important enough to document.

This relates to pull requests as well. Imagine you review some code of a colleague, and you want to propose some minor improvements. Will you write a comment, for example to ask to change the name of a variable? How is that helping? Why not simply do the work and push it? It will be easy to revert anyway. Rename that variable, identify that missing test case, format the code automatically, etc. Notify the author and see where the discussion takes you:

A comment that could be a commit, should be a commit.

I’ve encountered many teams where people feel this is bad form: you don’t change someone else’s work. To me this is at odds with the most fundamental reason why we construct teams: to be less dependent on individuals. If a single person owns a set of changes then you aren’t getting a lot of value out of being a team. So don’t feel bad about committing changes to amend someone else’s work because:

- By immediately putting in the proposed fix there is less work for the author;

- The proof is in eating the pudding: establishing if your proposal is any good, or possible even, is easier when you actually perform it;

- It reinforces the value that code isn’t owned by an individual, but rather by the team which reduces bottlenecks in the long-term;

- And again, it will be easy to revert;

That ability to revert is what makes version control so great, yet teams often seem to forget this superpower. Thinking of reverting is helpful too for establishing right-sized commits: what would you want to keep in case it turns out that this change is a step in the wrong direction?

Anything worth keeping on its own, should be committed independently.

Examples of this could be two or more distinct copy changes, some useful value objects that you implemented as part of a larger domain model, or removing multiple features. What happens if we flip that approach though?

Anything that must be removed at once, should be committed at once.

This one will often conflict with the previous heuristic, yet it may be helpful at times. Examples could be a set of interdependent configuration and code changes that don’t make sense on their own.

Some days things just aren’t working out. For example, when I started writing this article I started off in a different direction, which left me unsatisfied with the result. It is tempting to discard the work from a day like that, especially when it is “beyond repair” or in cases where it simply feels like “a stupid idea”. Though sometimes it is worth it to commit these ideas, followed by an immediate revert which explains why this direction isn’t optimal.

Implementations of bad ideas deserve to be remembered, for the team to consciously ignore and forget them.

Showing the things you have tried that didn’t work is often equally important given survivorship bias. A more refined and systemized approach to pain-driven refactoring is the mikado method which would benefit from this “commit, then revert” style.

Committing half-broken things, often it leads to raised eyebrows.

But what about the test? They will break the build?!

In an ideal world any moderately complex project with business value has CI/CD set up.

The point of such a set up is to increase the confidence of the team in frequent releases of the software.

Failing tests are an indicator that inform humans and deployment systems that releasing is a bad plan, and prompt them to investigate, they are the seatbelts of software development.

In order to know that a test is any good, it is best to write the test prior to the implementation and run it. I’m not saying that to repeat TDD to you, but that test should really be committed independently.

One of the other reasons for CI is to prevent the It works on my machine

discussions.

Pushing that failing test to trigger the CI/CD process, is a great favor to your coworkers.

They are now able to see that the test fails when it should, and when you push the implementation they can see the lights turning green.

Commits that break builds and by doing so increase confidence in the testing and deployment process, should be welcomed by the team.

With each refactor that is pushed, the team notices that the tests are passing: it didn’t change any behavior, it turned out to be a true refactor.

Any change that is supposed leave the system intact, should be committed independently and pushed immediately.

Remember that right-sized commits should reduce the burden of understanding the change. That extends beyond the commits itself, into the side effects it will cause.

How to get started

As with most things in life: practice makes perfect. Although you may consider talking about these ideas with your team, nothing should keep you from starting to do this already for the changes you commit yourself. Perhaps you will encounter people that don’t like the approach, that will be the best moment to have a conversation about the topic.

It helps to show people how the combination of right-sized commits, standardized commit messages, and pull requests, leads to lightweight code reviews from the reviewers’ perspective. If you classify various standard automated commits and agree on a message format, then you no longer have to review those commits on their content. You can put trust in the author not fumbling around with a machine-made (error-free) change. In the pull request you simply navigate through the individual commits (previous, and next) and focus on the actual discrete changes that matter. Perhaps followed with a final review of the diff in full. Moving through individual commits, being able to see how the thinking of the author matured, often provides more insight in why the author took a particular direction over another.

Yes, there may be many commits but only a few of them will be the meaty ones that need your input and scrutiny.

Notes on a messy mainline, squashing commits, and rebasing branches

An often heard argument against this approach is that the mainline will become messy.

The history should look clean

. I’ll spare you the joke involving totalitarian regimes.

One way people deal with this is by using tools such as git merge --squash to flatten all the individual commits into a single one.

Another approach is git rebase which results in a history without merge commits.

There are a number of issues with that approach:

- Horrible for external tooling: you miss the context and information associated with the individual commits from your CI/CD pipeline because the identifiers of each commit change.

- Easy to make mistakes: “Let me just force push this to the other machine. Oops, I accidentally removed part of our history.”

- It only works when everyone is in on the conspiracy otherwise people will hate you, and you’ll be scorned by friends and family.

This topic really deserves an article on its own, that’s why I recommend to read Why you should stop using Git rebase by Fredrik V. Mørken. It’s a great article that explains that rebase serves nothing but a vain purpose.

Discipline required

Perhaps you like what I described so far, but you’re still skeptical. You are right, some things that I described will only happen if you are going to bring up the discipline to show up at the commit dialog frequently. And only if you’re going to write better commit messages than: “changes” or “bugfix”.

There is a time, and a place to ignore these ideas. However, as with all approaches: you often need to do it far too much and far too little to know what exactly right looks like.

Reflection

These benefits in the end contribute to:

- Reviewing code from others will be simpler and more focussed;

- Better situational awareness when debugging;

- Effective knowledge sharing;

- A more experimental mindset;

- Non-sassy code-reviews;

- Less waste of energy (John is sick and hasn’t pushed his work yet);

- More transparency (I don’t know what John did on this last week);

Anyone who introduces “this is how I deal with VCS” thinks their approach is great. I think these are useful strategies but YMMV.

Further reading

- Atomic Commits by Pauline Vos: An approach that is similar in sizing, yet radically different in workflow.